On Tuesday 25 July, a severe fire broke out on the car carrier, the Fremantle Highway. Tragically, one crew member has been reported to have died, and the 22 rescued were treated for breathing problems and burns.

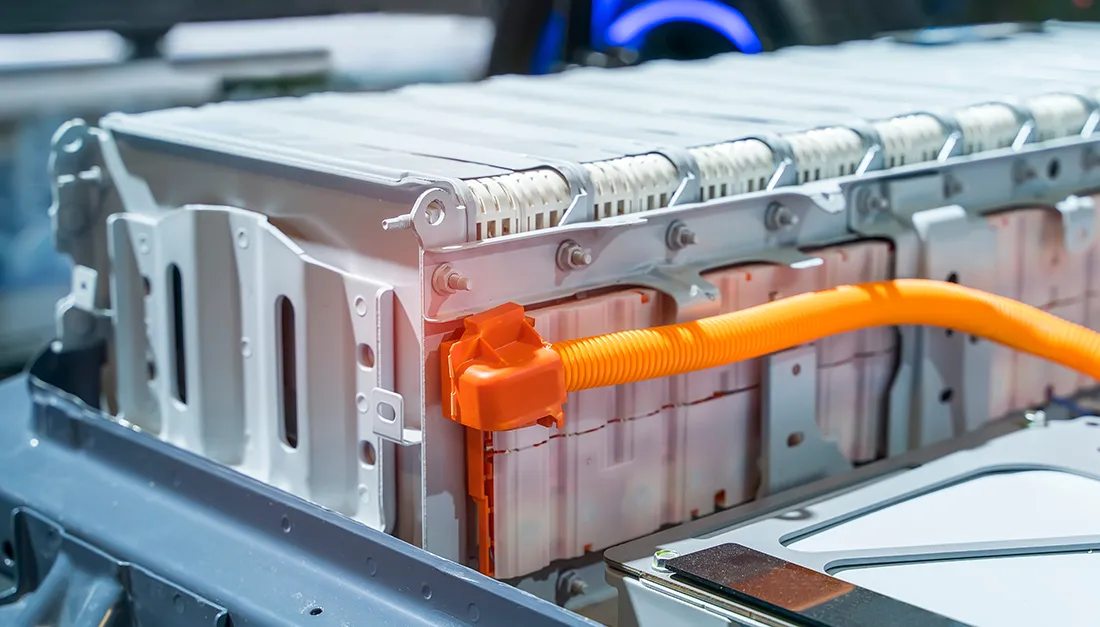

At the time of writing, the vessel is still on fire and the full extent of the injuries and losses sustained - and of the cause - is still unknown. What is known, however, is that the vessel was carrying 2,857 cars, 25 of which were electric vehicles. This casualty brings into sharp focus the ongoing safety debate around the carriage of products containing lithium-ion batteries.

As global connectivity, technological developments and consumer demand increase, so does the volume and range of goods carried by the shipping and logistics industry. Lithium-ion batteries and the products containing them – including computers, mobile phones, scooters, vapes and vehicles - have been subject to a rapid rise in usage over recent years. Such batteries and the products in which they are used need to be moved, stored and handled, and alongside this increased demand has been an increase in related fires.

The common law imposes a strict obligation on a shipper of goods not to hand over dangerous goods to a carrier without proper warning and sufficient information so as to allow the carrier to safely handle and carry the goods. The obligation is a strict one; the shipper is not relieved from liability simply because it was unaware of the risks posed by the cargo.

Most of the standard contract terms used in the logistics industry (including bills of lading terms and the standard contracts drafted by the trade organisations) adopt a similar approach to the common law with a strict obligation on the shipper.

However, the courts have long recognised that it is difficult to apply a rigid test to determine whether goods should be considered ‘dangerous’. The issue has to be considered in context. What information has been provided to the carrier or forwarder? Does the carrier hold itself out as being a specialist in moving goods of this nature? Do the goods in question pose a risk which is substantially different or greater than that ordinarily posed by goods of that description?

Many forwarders hold themselves out as specialists within industries or as having particular expertise in the carriage and handling of particular cargo. By so doing, they may also represent that they know about the risks posed by a particular cargo and the measures needed to ensure that it remains safe.

If a forwarder holds itself out as being a specialist in the carriage of electronic items or if it agrees that it is able and willing to carry goods which clearly contain lithium-ion batteries, the forwarder may well be accepting that lithium-ion batteries are not, in themselves, to be considered dangerous goods for the purposes of its contract with its customer. The forwarder may also be representing that it is aware of how to safely handle, store and carry such batteries and that it is familiar with the risks ordinarily posed by such goods.

That is not to say that forwarders are, in such circumstances, accepting lithium-ion batteries without any restriction or limits, including all risks of fire. If the lithium-ion battery is in good condition, it should pose very limited risk of fire. If the cargo owner hands over damaged or faulty lithium-ion batteries (which carry a much greater risk of fire) then those may well be considered to be dangerous goods and a special notification should be made. Even if the shipper is unaware of the fault or damage, it may breach its contractual obligations (either under the standard contract terms or at common law) by handing over goods which pose such an increased risk of fire.

When dangerous goods are stored or handled, the parties should exchange a Material Data Safety Sheet (MSDS) which details the risks presented by the cargo and measures to be taken in the event of an incident.

Regrettably, these documents are used without sufficient regularity in the forwarding and supply chain industry. However, when lithium-ion batteries are moved, such documents would provide a useful method by which a shipper can demonstrate that it has advised the carrier or forwarder of the risks inherent in the goods. Such documents are also useful for a carrier or forwarder when it comes to demonstrating that it followed the instructions and safety advice of the owner of the goods. Insurers may wish to investigate whether insured cargo owners or logistics providers are insisting on the use of these or similar documents.

Lithium-ion batteries are still evolving, and new technology is being developed and deployed on a continuing basis. As the batteries are developed, different types of batteries become available with different properties. Some of these batteries hold much higher charge, some hold their charge for longer periods, and some are safer than others. As such, there is quite a variance in the safety and risks associated with different types of lithium-ion batteries. Unfortunately, there are increasing reports of domestic fires and injuries caused by consumer goods with unregulated and faulty batteries. These goods are in the supply chain at some point.

These developments raise questions around whether the current safety regulations are sufficient to prevent or reduce the number of fires caused by lithium-ion batteries. The ADR (road carriage across Europe), the DGR (IATA’s air regulation) and the IMDG Code (for ocean carriage) adopt a rather broad-brush approach to classifying lithium-ion batteries as dangerous goods. These codes will need to be refined and updated to reflect the different types of battery available and the configurations in which such batteries are handled and transported.

The charity Electrical Safety First has recently published a report suggesting that lithium-ion batteries should be added to the list of high-risk products which require mandatory third party approval. This would result in an independent body testing and certifying all such batteries before they are able to be sold in the UK. If such testing and certification took place before the batteries are placed in the supply chain, it might reduce some of the incidents of serious fires which have hit the headlines recently.

Lithium-ion batteries are already widely used and their use seems certain to increase substantially. The government’s commitments to reduce carbon emissions and switch to electric cars can only add to this. As such, the logistics industry has little choice than to prepare itself for the carriage, storage and handling of lithium-ion batteries and products incorporating batteries. Logistics providers are already discovering that, increasingly, they are carrying such batteries even when this may not be expressly stated by the shipper.

As the risks associated with lithium-ion batteries become better known, forwarders who agree to move electronic goods may be holding themselves out as having an understanding of the handling, carriage and storage of such batteries. This may well have an impact on whether such goods are considered to be dangerous for the purposes of contractual exclusion and indemnity clauses.

This article originally published on Kennedys.